Aanjar, 58 kilometers from Beirut, is completely different from any other archaeological experience you'll have in Lebanon. At other historical sites in the country, different epochs and civilizations are superimposed one on top of the other.

Aanjar is exclusively one period, the Umayyad.

Lebanon's other sites were founded millennia ago, but Aanjar is a relative new-comer, going back to the early 8th century A.D. Unlike Tyre and Byblos, which claim continuous habitation since the day they were founded, Aanjar flourished for only a few decades.

Other than a small Umayyad mosque in Baalbeck, we have few other remnants from this important period of Arab History.

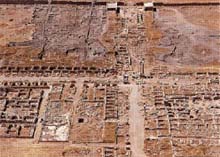

| Aanjar also stands unique as the only historic example of an inland commercial center. The city benefited from its strategic position on intersecting trade routes leading to Damascus, Homs, Baalbeck and the south. This almost perfect quadrilateral of ruins lies in the midst of the richest agricultural land in Lebanon. It is only a short distance from gushing springs and one of the important sources of the Litani River. Today's name, Aanjar, comes from the Arabic Ain Gerrha, "the source of Gerrha", the name |  Aerial view of the site of Aanjar |

|

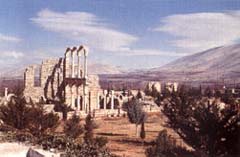

| of an ancient city founded in this area during Hellenistic times. Aanjar has a special beauty. The city's slender columns and fragile arches stand in contrast to the massive bulk of the nearby Anti-Lebanon mountains--an eerie background for Aanjar extensive ruins and the memories of its short but energetic moment in history. | ||

The Tetrapylon, a monumental entrance with four gates |

History,

Aanjar's Masters, The Umayyads The Umayyads, the first hereditary dynasty of Islam, ruled from Damascus in the first century after the Prophet Mohammed, from 660 to 750 A.D. They are credited with the great Arab conquests that created an Islamic empire stretching from the Indus Valley to southern France. Skilled in administration and planning, their empire prospered for a 100 years. Defeat befell them when the Abbasids--their rivals and their successors--took advantage of the Umayyad's increasing decadence. Some chronicles and literary documents inform us that it was Walid I, son of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, who built the city--probably between 705 and 715 A.D. Walid's son Ibrahim lost Aanjar when he was defeated by his cousin Marwan II in a battle two kilometers form the city. |

| Excavating

Aanjar Just after Lebanon gained independence in 1943, the country's General Directorate of Antiquities began to investigate a strip of land in the Beqaa valley sandwiched between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains some 58 kilometers east of Beirut. This was Aanjar, then a stretch of blend bareness with parched shrubbery and stagnant swamps that covered the vast area of these archaeological remains. The site at first seemed painfully modest, especially when compared with the rest of Lebanon's archaeological wonders. What attracted the antiquities experts to Aanjar was not such the ruins themselves as the information they held. Beneath the impersonal grayness of Aanjar, the experts suggested, lay the vestiges of the eighth century Umayyad dynasty that ruled from Damascus and held sway over an empire. That idea was particularly interesting because Lebanon--that unique crossroads of the ages--boasted ample archaeological evidence of almost all stages of Arab history with the exception of the Umayyad. Early in the excavation engineers drained the swamps. Stands of evergreen cypresses and eucalyptus trees were planted and flourish |

General view of the site

|

|

| today,

giving these stately ruins a park-like setting. To date, almost the

entire site has been excavated and some monuments have been

restored. Among the chief structures are the Palace I and the Mosque

in the south-east quarter, the residential area in the southwest,

the Palace II in the northwest and the Palace III and public bath in the northeast. |

||

The Cardo Maximus lined with shops |

To sense the vastness of the city, drive around the outside of the fortified enclosures before entering the 114,000 square-meter site. The north-south walls run 370 meters and the east-west sides extend 310 meters. The walls are two meters thick and built from a core of mud and rubble with an exterior facing facing of sizable blocks and an interior facing of smaller layers of blocks. Against the interior of the enclosures are three stairways built on each side. They gave access to the top of the walls where guards circulated and protected the town. Each wall |

Nearly 60 inscriptions and graffiti from Umayyad times are scattered on the city's surrounding walls. One of them, dated 123 of the Hegira (741 A.D.), is located in the western wall between the fourth and the fifth tower from the southwest.

Today visitors enter through the northern gate of the site but as the main points of interest are at the southern half of the city, it's better to walk up the main street to the far end of the site. You are walking along the 20-meter-wide Cardo Maximus (a Latin meaning a major street running north and south) which is flanked by shops, some of which have been reconstructed.

|

At the half-way point of this commercial street a second major

street called Decumanus Maximus (running east to west) cuts across

it at right angles. It is also flanked by shops. In all, 600 shops

have been uncovered, giving Aanjar the right to call itself a major

Umayyad strip mall. The masonry work, of Byzantine origin, consists of courses of cut stone alternating with courses of brick. This technique, credited to the Byzantines reduced the effects of earthquakes. The tidy division of the site into four quarters is based on earlier Roman city planning. At the city's crossroads you'll have your first hint that the Umayyads were great recyclers. Tetrapylons mark the four corners of the intersection. This configuration, called a tetrastyle is remarkably |

The Great Palace |

|

| reminiscent

of Roman architecture. One of the tetrapylons has been reconstructed

with its full quota of four columns. Note the Greek inscriptions at

the bases and the Corinthian capitals with their characteristic

carved acanthus leaves-delightful to look at but definitely not

original to the Umayyads. A city with 600 shops and an overwhelming concern for security must have required a fair number of people. Keeping this in mind, archaeologists looked for remains of an extensive residential area and found it just beyond the tetrastyle to the southwest. However, these residential quarters received the least attention from archaeologists and need further excavation. Along both sides of the streets you'll see evenly spaced column bases and mostly fallen columns that were once part of an arcade that ran the length of the street. Enough of these have been reconstructed to allow your imagination to finish the job. The columns of the arcade are by no means homogeneous; they differ in type and size and are crowned by varying capitals. Most of them are Byzantine, more indication that the Unayyads helped themselves to Byzantine and other ruins scattered around the area. |

||

Reconstructed fašade of the Great Palace

|

On your way to the arcaded palace ahead, notice the numerous slabs

of stone that cover the top of what was the city's drainage and

sewage system. These manholes are convincing evidence of the city's

well-planned infrastructure. The great or main palace itself was the first landmark to emerge in 1949 when Aanjar was discovered. One wall and several arcades of the southern half of the palace have been reconstructed. As you stand in the 40-square-meter open courtyard, it is easy to picture the palace towering around you all four sides. Just to the north of the palace are the sparse remains of a mosque measuring 45x32 meters. The mosque had two public entrances and a private one for the caliph. If you enjoy a good game of archaeological hide and seek, the second palace is the place for you. It is decorated with much finer and more intricate engravings, rich in motifs borrowed from the Greco-Roman tradition. Very little reconstruction has been done to this palace so its floors and grounds are in their natural state. With patience you will |

More evidence of the Umayyad dependence on the architectural traditions of other cultures appears some 20 meters north of this second palace. These Umayyad baths contain the three classical sections of the Roman bath: the vestiary where patrons changed clothing before their bath and rested afterwards, and three rooms for cold, warm and hot water. The size of the vestiary indicates the bath was more than a source of phisical well-being but also a center of social interaction. A second, smaller, bath or similar design is marked on the map.

Aanjar Today

Aanjar is open daily. Close to the ruins of Aanjar

are a number of restaurants which offer fresh trout plus a full array of

Lebanese and Armenian dishes. Some of the restaurants are literally built

over the trout ponds. Aanjar has no hotels but lodging can be found in

Chtaura 15 kilometers away.

If you have time

Ain Gerrha. Aanjar's major spring is located 3 kilometers northeast of

the ruins.

Majdal Aanjar. A Roman period temple sits on a hilltop overlooking

this village, which is one kilometer from Aanjar.

The Mausoleum of El-Wali Zawur is the burial spot of a religious

personage from medieval times. Until the early 1980s fertility rites were

held here.

Kfar Zabad. Roman temple ruins and a cave with stalactites and

stalagmites. Special equipment needed for the cave.

(BEIRUT - BYBLOS - JEITA GROTTO - TRIPOLI - SIDON - ZAHLÉ - BAALBECK)

(THE CEDARS - TYRE - BEITEDDINE)

EGYPT - SYRIA - JORDAN